Widowed and possibly lonely, with her strength ailing and stricken by doubts, the last will of Cosmana Navarra in 1684 has a tone of troubled urgency.

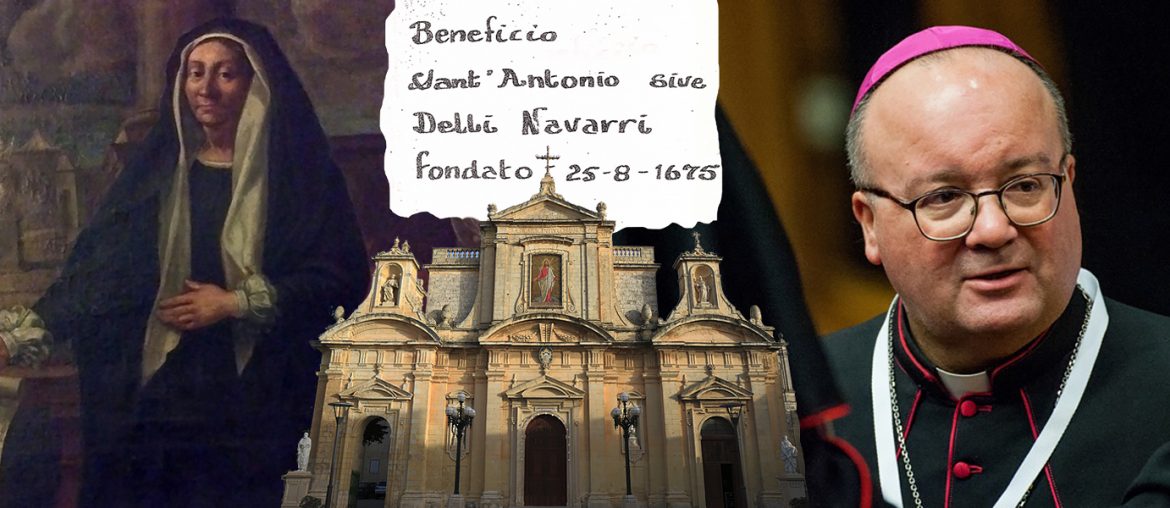

She doubted whether she would complete St Paul’s Church, her most enduring project, before her death. And she doubted whether sufficient funds could be raised for pious deeds through the foundation called Beneficcju ta Sant Antonio delli Navarra, which she had set up.

Cosmana wrote that will – at 84 years old – to address those doubts. She eventually died three years later.

The noblewoman, who lived in a large house in Rabat’s town square, had lived through loss and death – the death of her two husbands and her son, and a plague pandemic (Malta’s deadliest ever) that had killed an estimated 11,000 people.

She had set up the foundation in the months before that plague outbreak, in 1675, putting vast lands she had inherited in Gozo in the foundation whose point was to raise money for pious deeds.

More than three centuries later this has now given rise to what has become known as the Gozo land grab – you can read the timeline by clicking here.

At the archbishop’s pleasure

According to the court-commissioned Maltese translation of the Latin deed, by Malta’s most eminent Latinist, Profs Horatio Vella, Cosmana used the term at the archbishop’s pleasure to define the archbishop’s overarching faculties or powers in the foundation. In this sense, the archbishop had to have the “pleasure to accept” her descendants’ nominee for rector to administer the foundation, and any transfer of land via emphyteusis (lease) by the rector was subject to the archbishop’s pleasure.

This gave the archbishop the power of veto, or discretion, which shows the trust Cosmana had in archbishops.

And that’s a context that is different from the characterization offered by Archbishop Charles Scicluna during testimony in court last November. He defended the decision to “renounce the right” to give his consent over land transfers by latching onto a court judgement in 2010, which held that the foundation was lay not religious. Scicluna said that he felt that the archbishop should not have to give his consent for every land transfer of a lay foundation.

Yet the judgement Scicluna latched onto was overturned by a higher court 3 years later. And, as paralegal Tony Cassar emphasized in his speech outside the Curia last month, it’s the final judgement that matters – and in the final judgement, the church won the case, all its expenses paid.

Moreover, Cosmana vested powers in the archbishop irrespective of whether the foundation fell under civil or ecclesiastical law.

To understand fully the inexplicability of Scicluna’s decisions, you have to consider Cosmana’s life and sensibility, and how the archbishop was part of her plan in the foundation she set up “for all future time.”

Nobility and religiosity

It all started in the fifteenth century when two members of the Navarra family followed King Martin I from their home in Spain to Sicily. One of them, Andrea Navarra, then emigrated to Malta and was reportedly installed as governor for Gozo.

It’s not clear whether Cosmana's land in Gozo, which was put in the foundation, was acquired at that time. (In the Medieval Ages much land in the Maltese Islands was held in fiefdoms of Sicilian merchants.)

According to the late priest and scholar Gwann Azzopardi, Cosmana’s mother Cornelia was born from Andrea’s lineage three generations later. She married Giovanni Cumbo, another noble, and gave birth to Cosmana in 1600.

Cosmana married Melchior Vella, a lawyer who hailed from a family of priests – three of his uncles were priests, including the then-archbishop Baldassare Cagliares. Melchior and Cosmana had a son, Injazju.

Then Cosmana’s life entered a stretch of loss and grief. Her husband died when Injazju was still young, and Injazju – who became a Jesuit and studied philosophy in Naples – died in young adulthood. She married again, but death also eventually took her second husband.

Historical sources report that she ended up nurturing her “slave’s” son, Moses, who became a priest.

Building St Paul’s Church

Cosmana accumulated wealth and property through inheritance. Aside from the vast lands in Gozo, some historical papers also mention land in Bahrija and Palazzo Falzon in Mdina (now open as a historic house museum).

In 1653 she embarked on her life’s most ambitious project: the reconstruction of St Paul’s Church in Rabat.

She engaged the Knights’ resident architect, Francesco Buonamici, and, when he left Malta, assigned the project to Lorenzo Gafa. The latter is Malta’s most famous church architect – he also designed St Paul’s Cathedral in Mdina, St Lawrence’ Church in Vittoriosa, St Catherine’s Church in Zejtun, and Gozo’s Cathedral.

Construction took 30 years, from 1653 to 1683, and it was reportedly bogged down by funding shortfalls at one point. Although historical details are sketchy, it appears that Cosmana struggled to fulfill pious deeds under obligations attached to some land she had inherited.

Perhaps it was these experiences that contributed to her doubts, and later led her to empower the archbishop in rules of the foundation she set up to raise funds for pious deeds.

Anxiety over fulfillment of pious obligations

By 1684 she was worried that she would not complete St Paul’s Church before her death and that not enough funds for pious deeds would be raised from the foundation.

So in the will of 1684, 3 years before her death, with its tone prescriptive and urgent, she laid precise obligations on her heirs. This included a range of pious deeds they had to fulfill if insufficient funds were raised from the foundation one year after her death, as well as detailed instructions for the completion of St Paul’s Church.

The sensibility expressed in that will as well as Cosmana’s life experiences suggest that, 9 years before when she set up the foundation, she had felt that vesting decisive power in the archbishop would ensure adherence to the foundation’s rules. She set up the foundation for her descendants and she obligated the administrative rector to fulfill the pious deeds, but it’s the archbishop she trusted with decisive, veto power.

That all changed in the two contracts signed on behalf of Archbishop Scicluna in 2017 and 2018. The archbishop appointed a rector who is neither a descendant nor a priest – something that deviated from the rules of the foundation. The rector then began trying to evict people from homes and lands they have held for generations, and started transferring foundation lands to companies which are now making millions from development of flats. Dozens of residents have been driven to anxiety and sickness.

Yet in the decree that authorized his legal emissary to sign the first contract, the archbishop wrote that the decision was taken in the interest of the family and the church and the foundation. Asked last year whether the rector transferring the most valuable lands of the foundation to companies was in the longterm interest of the foundation, the archbishop did not reply.

He has since said in his testimony that the rector is not supposed to “touch” the land, and has to keep foundation land “intact.”

But Scicluna has not responded to requests made by residents and Moviment Graffitti a month ago outside the Curia to dismiss the rector and initiate legal proceedings against the land transfers.

The only response has been a press release published on the church’s website that’s riddled with spin if not lies.