The statistical array into domestic violence published last Tuesday by the National Statistics Office (NSO) led to confusion – and sensationalist and incorrect, or false, headlines in mainstream news platforms about increases in domestic violence reports.

The statistics were published under a theme – Domestic Violence 2021 – in which the NSO detailed the number of victims of domestic violence making use of various services offered by the State. The services include shelters for domestic violence victims, services run by the social work agency Agenzija Appogg, and the police. The statistics showed a statistical growth in the use of such services, but numbers were a tally of multiple times of use of such services by each person.

In the “Salient Points”, the NSO was equivocal by stating that “compared to 2020, persons making use of such services during the reference year increased by 12.9 per cent in 2021.” This was clarified under various tables and graphs by this caveat: “Individual cases are recorded by the service provider each time a person accesses the service during that reference year. Therefore figures include persons making use of services more than once.”

Yet newspaper headlines then suggested that the NSO had found a growth in the number of domestic violence reports even though the NSO statistics did not feature any trends in domestic violence reports from year to year as such. The Times of Malta’s headline held that the rise in reports was “substantial”, while Malta Today’s headline held that reports in 2021 climbed by “13% over previous years.”

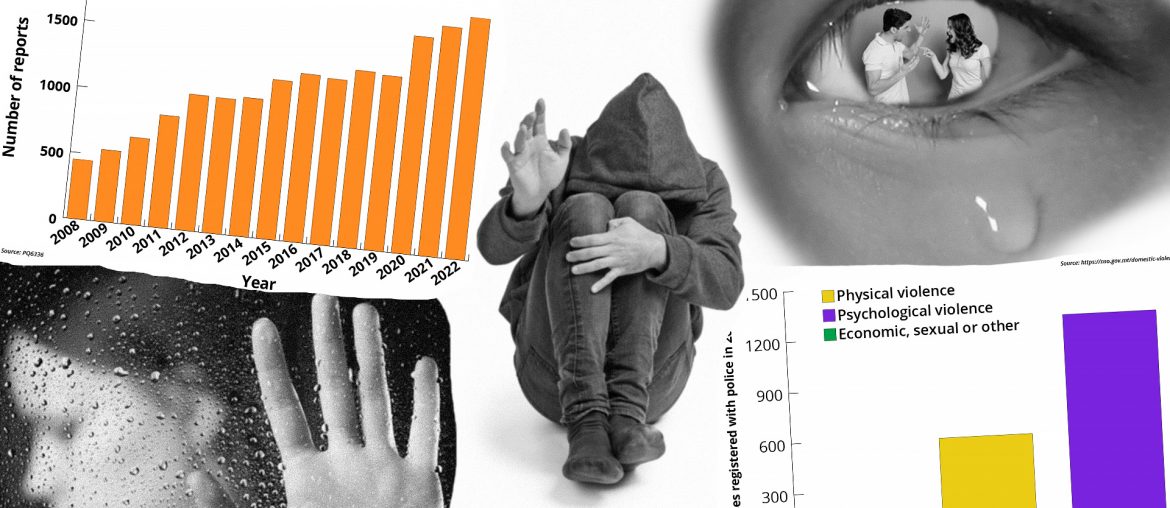

The actual number of domestic violence reports over the years can be found in figures presented in parliament earlier this year (parliamentary question no 6336). According to those figures, the number of reports in 2021 amount to 1741, up from 1645 in 2020. This transmutes into a six percent increase in domestic violence reports from year to year.

Of greatest analytical interest in the data published by the NSO is the breakdown of police data on type of violence registered with the police in 2021. These numbers are categorised into three types of violence: physical, psychological, and a third category called ‘economic, sexual or other.’

What emerges clearly is the preponderance of psychological violence – the statistics show that 68 percent of all cases registered with the police to be psychological violence.

Reports of psychological violence have grown steadily in the past decade as a proportion of total reports of domestic violence.

Domestic violence, which is punishable by up to 4 years imprisonment, is defined in law as “verbal, physical, sexual, psychological or economic violence causing physical and, or moral harm or suffering, including threats of such acts or omissions, coercion, or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, that occur within the family or domestic unit, whether or not the perpetrator shares or has shared the same residence with the victim, and shall include children who are witnesses of violence within the family or domestic unit.”

The complication with psychological violence is that – even though it can be insidious and debilitating – it is very hard to prove or disprove in court. Gathering evidence would entail a psychological assessment involving clinical interviews with all parties, including any children, but these would make proceedings lengthier and costlier and more complex – and psychological assessments are not conducted as a matter of course in investigations.

Around four in five of all criminal prosecutions of domestic violence end up in acquittal. Aside from allegations remaining unsubstantiated – mostly in the area of psychological violence – other reasons for this high acquittal rate include inadequate police investigations, and alleged victims refusing to testify (reasons for this include victims not wanting to see the father, or mother, of their children be damaged or separated from children by a criminal conviction, as well as couples reluctant to destablise any hard-won out-of-court separation settlement).

Another complication is the phenomenon of false allegations of domestic violence – as well as child abuse – in the context of marital separation proceedings. Domestic violence can lead to protection orders, temporary custody of the children, and maintenance payments (Article 37 [2], and Article 47 of the Civil Code). And one tactic that some parties use is to file for separation and claim domestic violence, mostly psychological violence, in an attempt to get temporary child custody and maintenance payments, and evict the other spouse from the house. The temporary can then become permanent as court cases drag out for years in court.

There have been no studies that quantify the phenomenon of false allegations of domestic violence in the context of marital separation. False allegations of child abuse in the context of separation proceedings are better quantified – some studies suggest that the proportion of false allegations of child abuse amounts to up to three-fourths of child abuse allegations that arise from one of the parents, and up to 15 percent of abuse allegations that arise from the children themselves.

In the case of domestic violence allegations, discussions I have had with sources in police, court, and social services suggests that a substantial number of domestic violence allegations that arise in the midst of separation proceedings are false.

False allegations are damaging to – and distraction from – the real cases of domestic violence. And, as an analysis published in this website last week posited, changing the dynamic from winning or warfare to cooperative shared parenting in the family court is one of the keys to freeing resources, and dispelling wariness and weariness, in order to tackle domestic violence more effectively. It is also key to averting damage to children’s psychological development, as detailed in a report on the science of shared parenting I researched and published. Click on the banner below to open the interactive report.

Sustain Analyses & Insight

This website does not have backing of advertisers or sponsored articles: the robustly researched and professionally delivered analyses and insight features you read here are funded by reader's donations. The donation setup itself is uniquely transparent, with targeted amounts – of just €50 every month for analyses – that allow tracking of donations in real time on the page. Contribute as little as €5.