I used to be served at the local petrol station in a village in Gozo by a young man who was always ready with a boyish chuckle. We used to make small talk. Then one day there was someone else filling customers’ fuel tanks at the station, a young African refugee.

Sometime later I saw the young man with the boyish chuckle again one early morning in a street in a residential area. This time he had a broom and shovel, and he was sweeping up scatters of litter or plants appearing in cracks between pavements and road.

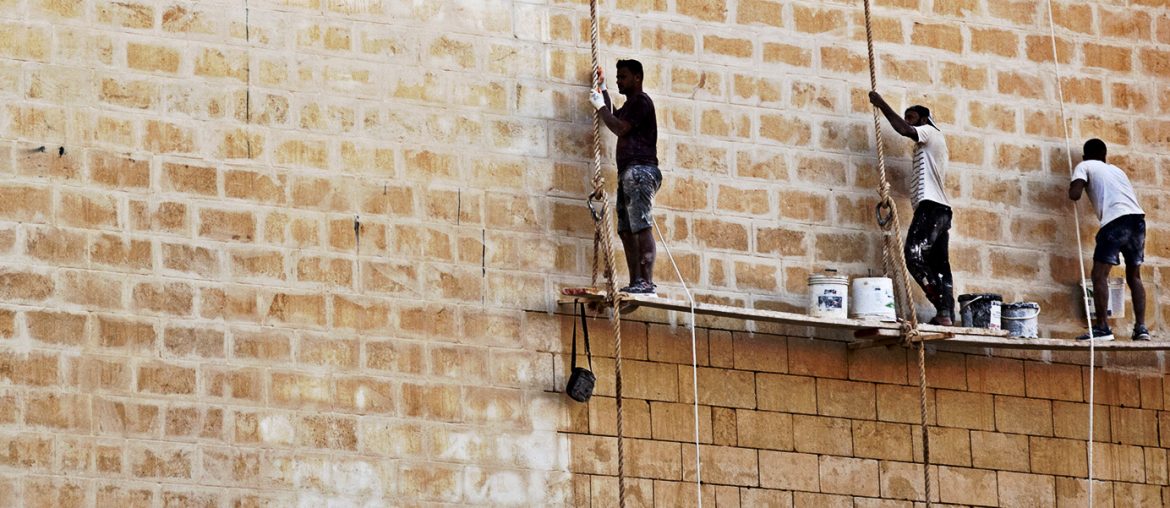

Large construction companies in Gozo employ hundreds of Albanians

There was hardly any litter on the street. We are talking of a residential area where most residents still make it a habit to sweep the patch of road in front of their houses.

But I suppose that was part of the point of switching jobs – an opportunity to work less. The young man had become a community worker, recruited by the Community Workers Scheme, which has since 2016 become a route to bypasses normal recruitment procedures into State-attached jobs. It has been dubbed in some media quarters as a “jobs-for-votes” scheme, and the latest statistics – given in parliament last week – show that 176 community workers were engaged in the two months leading up to the general election last March.

The scheme was originally devised in 2009 for those on the unemployment register for longer than 2 years, obliging them to work with public entities, mostly local councils, and topping up their unemployment benefits. Their topped-up benefits still amounted to less than they would earn if properly employed; the point of the scheme was to incentivize them into finding a more productive job with the private sector.

The scheme began to change in 2016. It was outsourced to a foundation established by the General Workers Union, the Community Worker Scheme Enterprise Foundation, and community workers were given the right to paid sick leave and vacation leave and their salary raised to the minimum wage. The salary was raised again in 2018, bringing it up to the current level of around a €1,000 a month including yearly bonuses.

The contract with the foundation specifies that two types of people can be engaged – the long-term unemployed and a second undefined category called “additional resources”, which has since become a loophole.

Most workers do not do more than a handful of hours of work every day, and some of them – most notably beach cleaners in Gozo – spend around an hour or less at work every morning.

Gozo holds the largest proportion of community workers. According to the latest statistics given in parliament, Gozo has 502 out of the national total of 1,153 community workers. That means Gozo – with less than 10 percent of the national population – has 44 percent of community workers.

A report by the National Audit Office in 2019 found that the scheme cost the State €15 million annually, a figure that has now swollen because the number of community workers is now several hundred more than it was then.

The Malta Employers Association called for phasing out the scheme in last year’s budget proposals. The MEA told Business Now website at the time that the scheme “should be a pathway for persons to move towards productive employment”, and spoke of “the need to free [up] and incentivize underutilized labour and channel it into more productive employment in the private sector”.

But the government moved in the opposite direction, recruiting almost an additional 200 community workers in the runup to the election.

In Gozo, the number of community workers now amounts to 1 out of 25 Gozo-based workers (Gozo has 12,304 workers, according to National Statistics Office).

Every small business in Gozo has a story of a worker lost to a government job, either as a community worker or some other form of worker deployed to serve the State (security officers, soldiers, and so on).

My local panel beater, for example, has been unable to find a worker for many months after one worker left to join the community work scheme and another to join the army.

This is one of the main factors that has been compelling small companies to resort to imported labour.

Such reliance is demonstrated by a press statement issued by The Chamber for SMEs last Wednesday. The chamber, which represents small and medium enterprises, expressed their “highest alarm” at the lengthy processing times for applicants from “India, Nepal, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Maldives” applying for work visa. The chamber said these countries have become “exceptionally important sources of personnel.”

The chamber described the situation as a “human resource crisis” that is costing the country “several million.”

Imported cheap labour is not limited to south Asians. Large construction companies in Gozo for example employ hundreds of Albanians.

Yet even as the cloggage in visa processing is costing “several million” according to the chamber, the country is simultaneously squandering many more millions every year in salaries of community workers that, according to the Malta Employers’ Association, can be “absorbed” in productive jobs in the private sector “with minimal training.”

The problem of overstaffing and absenteeism in State entities is of course wider than community workers. The latter are among the most visible, but there are thousands of superfluous workers attached to the State – I use the word attached to include those on contract of service, or employed by private companies contracted for the State service (such as security guards, for example).

The price we are paying is not only limited to the burden on taxes and economic efficiency. It is also social or moral. The community worker scheme, for example, fosters a culture of corruption and sloth. And, in an indirect way, it also plays a part in the dynamic that has made us insensitive to the exploitation of workers from poor countries.

Donate to Insightful Journalism

Victor Paul Borg relies on donations for income for work published on this website – which is distinctly well-researched and professionally delivered. This website's donation setup itself is different and uniquely transparent, with targeted amounts that allow tracking of donations in real time on the page. Contribute as little as €5 to sustain active journalism that makes an impact.