Key Findings

- Stalled court proceedings complicates outcome of eventual trials

- Legal sources have never seen such delay, which creates a sense of impunity

- Separate magisterial inquiry in Malta also stalled

- Company involved gave pre-election donation to Malta’s parliamentary secretary for fisheries

- No comment from parliamentary secretary about Marsaxlokk office in fisherman's building

- Former director of fisheries is on long-term unpaid leave to find alternative employment

- Spanish farm ordered to release number of tuna amounting to around 1.2 million kg in weight

- Details of how tuna was moved from Malta to Spain

- Mole in Spain’s Civil Guard who leaked information undergoing prosecution

- Industry talk of illegal tuna fishing remains widespread

It was in the industrial area that envelops the small town of Beniparrel, a town of less than 2,000 people adjacent to one of Spain’s most important wetland habitat, that the Spanish Civil Guard swooped on a nondescript warehouse after an intense investigation into one of Europe’s most lucrative fish smuggling and trading rackets. The swoops at two locations in Spain yielded 79 arrests, 80,000kg of illegally-caught bluefin tuna, around half a million euro in cash, half a dozen flashy vehicles, and other objects.

The Civil Guard’s extrapolations were even more staggering: they estimated an annual profit from the racket of 12 million euros, and an annual flow of illegally-caught tuna from Malta alone amounting to 2.5 million kilograms.

The investigation might have yielded wider evidence and more plotters had it not been for a mole within the Civil Guard who alerted one group of racketeers and, separately, a decision to pounce prematurely that was taken after a person ended in hospital as a result to food poisoning. In fact one of the things that emerged in the course of the investigation is of the fish treated with additives to mask signs of spoilage, such as smell, caused by improper transport and storage.

Consumer laws were not the only laws allegedly breached. And despite cutting the investigation short, the Civil Guard – this is Spain’s gendarmerie force, distinct from the police – in their investigative report described an organized crime enterprise spanning Spain and Italy and Malta, and serious offences including fraud and money laundering.

The investigation was called Operation Tarantelo, and, given the geographical spread of the criminal activity and the magnitude of the case, the provincial court in Valencia sent the case to the Audiencia Nacional (National High Court) in Madrid. That was three and a half years ago – and there has since been virtually no progress in the case.

Judicial investigations in Spain (and Malta to a less important extent) have stalled.

And a journalistic investigation that is being published in Italy, Spain and Malta simultaneously can now report that this has contributed to a sense of impunity.

The high price of tuna – an adult tuna is worth thousands of euros; in Spain it costs €30-40 per kilo to consumers – has long encouraged illegal fishing and even attracted organized crime elements.

Overfishing nearly drove tuna to extinction around 15 years ago, and although aggressive cuts in catch quota and regulations has led to an increase in the population, the fishery is still under a population-recovery regime imposed by the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tuna (ICCAT). The understanding is that controls have to remain tight to prevent any backsliding to the time when the tuna population plummeted due to overfishing.

Yet the stalled proceedings in Spain – and Malta – undermine the element of deterrence, which is needed to disincentivise illegal fishing.

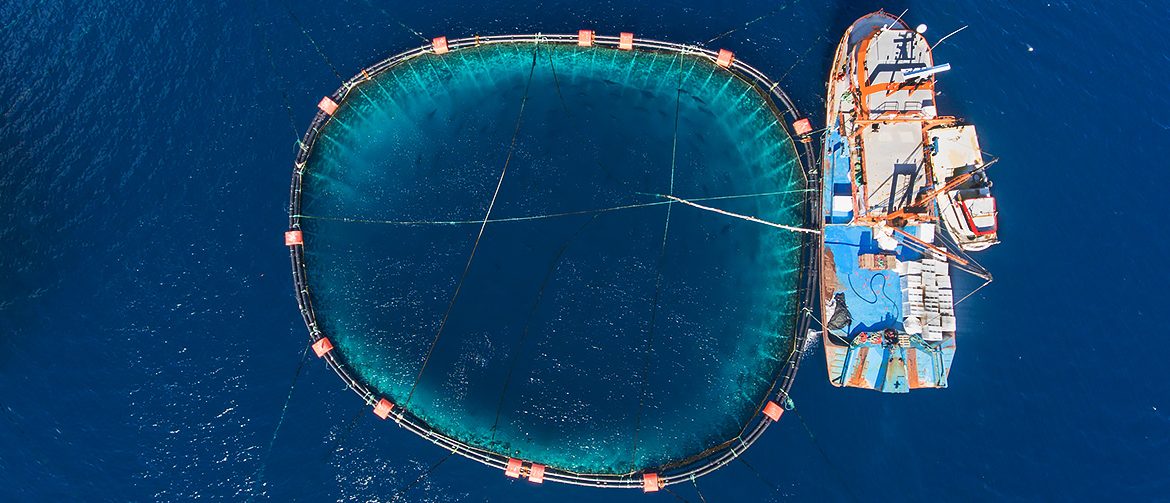

Talk of illegal fishing within the industry remains widespread, and sources have given information on alleged illegal caging of tuna by various farms. (The tuna fattening industry works by caging tuna caught in the wild and feeding it for a few months to increase its fat-to-meat content, then slaughtering it and selling it mostly to Japan for sushi and sushimi market.)

This includes Spain’s Grupo Ricardo Fuentes e Hijos SA, which according to sources in the Civil Guard, were this year allegedly ordered by the Spanish Ministry for Agriculture and Fisheries to release an excess number of tuna amounting in weight to some 1.2 million kilograms from one of their tuna fattening farms in Spain. (The Fuentes group also has a tuna fattening farm in Malta.)

Responding to questions, a spokesperson for the Fuentes group did not dispute the figure. The spokesperson said that such situations are normal or standard within the tuna farms, insisting that there “has been no sanctioning proceedings whatsoever.”

Questions sent to the Spanish fisheries ministry about the same case were not answered.

Legal time-term for statements set to expire

The delay in Spanish proceedings makes a vast, complicated case more complex still, and the outcome more uncertain and contestable. In the Spanish legal system, there are two phases to criminal proceedings: the investigative phase (when statements are taken, evidence analysed, and further probes conducted) and then the trial phase. The Tarantelo case – presided by the judge Maria Tardon at the Audiencia Nacional – has stalled at the investigatory phase.

Although the evidence collected by the Civil Guard appears to be considerable and robust, sources said that the protagonists have not yet been summoned to give statements. The sources also said that the judge has now asked the parties for an extension of the legal time-terms for getting depositions (sworn statements), which was due to expire this September. The extension is a formality, but it will give more traction to those who would potentially face trials to eventually invoke Article 21 (6) of the Spanish Criminal Code, which holds that delays can be a “mitigating” factor in setting punishment if the accused or convict is not to blame for delay, and if the “prolongation [is] disproportionate to the complexity of the cause.”

The Tarantelo case is complex, and a year ago Spanish judicial sources told an IRPI-led investigation that letters rogatory sent to Malta remained unanswered until then. The ongoing, separate magisterial inquiry in Malta that has also dragged on. It is also understood that Panamanian authorities have not supplied information on offshore companies of some of the protagonists held in Panama , which is where some of the proceeds from the racket were spirited according to the Civil Guard.

Some sources believe that one reason for the stalled proceedings is due to the court’s workload and priorities.

A Spanish legal source who spoke on condition of anonymity said that he has “never seen” in years working in the legal system “a case delayed to such an extent.”

He added: “I fail to understand this undue delay in the process, it creates a situation of impunity among the defendants.”

Celia Ojeda, head of biodiversity and consumption at Greenpeace Spain, said that she worries that the prosecution will eventually collapse.

Ojeda said: “We need prosecutions to show people and politicians that illegal fishing has been happening, and also to show companies that if they are involved in illegal fishing, they will face consequences. There is also a consumer issue: they were putting unhealthy tuna on the market.”

Greenpeace Spain are involved in the case as a so-called private prosecutor together with two other entities – Balfego, a Spanish company that farms and trades in bluefin tuna, and Cepesca, the association of owners of fishing vessels in Spain.

According to sources, the Spanish Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food also engaged a State lawyer – the State Lawyer Corps in Spain are part of the Ministry of Justice – to participate in the case. This was announced by the Minister when the story first came out and caused disquiet in Spain. Yet the sources said that the Ministry or the State Lawyer have since not done anything to urge the judge to proceed with the case. A State Lawyer could file a legal application requesting movement in the case, something that, according to sources, has not been done.

The Ministry did not reply to questions on this and other points.

The sources said that it was one or more than one of the other private prosecutors who filed applications urging the court to proceed with the case. According to the sources, the judge did not respond to such application or applications.

In their investigative report, the Civil Guard highlighted that the activities investigated – aside from fraud and money laundering, and consumer-related laws – fit within the provisions of Article 334 of the Criminal Code: fishing, acquisition, possession, and trafficking of a protected species, and illegal fishing that “prevents or hinders its reproduction or migration” – after all, the report said, the bluefin tuna had migrated into the Mediterranean Sea to spawn. Punishment for breaches of Article 334 ranges from a fine to two years imprisonment and a suspension of fishing or trading license (and the right to fish or hunt) of between two and four years. Yet once again, the delay in court proceedings sends an unwitting or subliminal message of impunity.

The protagonists in this investigation include some of the biggest players in the tuna industry. These include the fish distributors Marfishval and sister companies in Spain; Ricardo Fuentes e Hijos – the Fuentes Group have dozens of companies in various countries, mostly involved in the tuna industry, including a tuna fattening farm in Malta; the Red Fish SRL distributor in Sicily, one of Sicily’s largest fish distributors for tuna and swordfish; and Malta Fish Farming Limited (MFF Ltd), which has a tuna fattening farm and other fishery operations, and whose owners also own Ta Mattew Fisheries Limited.

The Civil Guard’s investigation also yielded telephone intercepts between Jose Garcia Fuentes of the Fuentes group and the then director general of the Department of Fisheries and Aquaculture in Malta, Andreina Farrugia Fenech. Fuentes was communicating with Farrugia Fenech on a mobile phone with a Spanish number registered to the Fuentes group, and the Civil Guard reported that there was “absolute trust” trust between the two of them, and that Farrugia Fenech had detailed knowledge of operations pertaining to Fuentes’ fattening farm in Malta. In the phone transcripts, the two of them discussed Fuentes’ endeavour to increase the capacity of the tuna farm in Malta. Farrugia Fenech was also overheard saying at one point that he had to pay her.

Fenech Farrugia was suspended from work in 2019. Yet she remains technically employed, and for over a year now she has been on long-term unpaid leave – extended again earlier this year for another year – on the basis that she is seeking alternative employment in the private sector.

Contacted for comment – and asked if she had given depositions (sworn statement) to the magistrate holding the judicial inquiry in Malta – she declined to comment.

Donation to junior fisheries minister

Giovanni Ellul, director of the Maltese company MFF Ltd, one of alleged suppliers of illegally-caught tuna to Spain, has had a brush with the law in the past over tuna operations. In 2016 Ellul pleaded guilty in the Maltese criminal court to possession of an unspecified amount of illegally-caught or undocumented tuna as well as making a false declaration to a public authority. The sanction was low: a fine of €1,500, with his guilty plea and clean criminal record weighing in as a mitigating factor.

Both Ellul in his personal capacity and MFF Ltd as a legal entity are listed among the protagonists in Operation Tarantelo.

Earlier this year, MFF Ltd donated €2,500 to the electoral campaign of Alicia Bugeja Said, who stood for general election for the first time on 26 March 2022. She was elected and made junior minister responsible for fisheries and aquaculture, which includes tuna fishing and farming.

The €2,500 donation represents more than 20 percent of the total of donations raised by Bugeja Said for her electoral campaign. Another donation of €1,500 was made by Azzopardi Fisheries, which is owned by a businessperson who is the main owner of two tuna-ranching companies in Malta.

Bugeja Said declared that she received a total of €11,000 in donations, and this means that more than a third of donations in Bugeja Said’s electoral campaign came from two of the four lines of ownership or group of companies that own Malta’s tuna fattening farms.

Bugeja Said, who studied conservation and anthropology, used to be extremely critical of the tuna fattening industry. In a paper published in 2016 in a journal called Marine Policy, Bugeja Said and two other scientists wrote about the situation in Malta: “The transition into [tuna] ranching has been highly welcomed and incentivised by the national government and although this transition is lauded as a tool of ‘diversification’ for fishers, in reality, it is a policy that is serving the elitists’ interests, and simultaneously obliterating the artisanal [fishing] sector.”

The author continued in this vein, writing that “the economic power of the tuna ranching industry and the concomitant individualistic pursuits of the co-operative representatives, which have been invisibly taking place within the ambit of the liberal market transactions, are suffocating the artisanal segment and deteriorating the political capital of the Fishermen's Co-operative as a united force.” She added that “fishermen have basically succumbed to the powerful forces of industrialists who allegedly have the inside track to senior politicians.”

Malta’s tuna farming industry, which has the largest capacity in the world, generates more than €150 million annually.

Six years after that paper in Marine Policy, Bugeja Said is now a parliamentary secretary in charge of Malta’s fisheries sector.

Bugeja Said did not respond to questions on whether it was appropriate to accept donations from MFF Ltd in view of the activity documented in Operation Tarantelo and the conviction of one its directors in Malta’s criminal court.

Prior to the general election, Bugeja Said opened an office in Malta’s main fishing port of Marsaxlokk (she still receives constituents at the office every Thursday afternoon). The office is on the ground floor of the house of a fisherman’s family who fish for swordfish and tuna with longline. The fishermen – who catch tuna with hooks attached to fishing lines several kilometres long – are considered small-scale in Malta. Longline fishing is less intensive and less impactful that the purse seine fishing, which catches tuna live for tuna fattening farms.

Bugeja Said did not reply to a question on whether she pays rent for the office in Marsaxlokk, and how much, or any other question put to her.

Neither did the spokesperson of the department she runs respond to a separate set of extensive questions.

EU sources told his website that the EU Commission is currently analyzing the situation to decide whether to take Malta to the European Court of Justice for what the Commission last November said were systematic failures including “delayed investigations” and failure “to put in place an effective monitoring, control and inspection system for Bluefin tuna farming activities.”

The parallel plots

The intense investigation by the Civil Guard, detailed over hundreds of pages, covered 28 companies and 86 people, some of them even tasked with collecting and couriering tens of thousands of euros in cash in backpacks.

The Civil Guard discovered two parallel, yet separate rackets, in what it termed as the Valencia plot and the Murcia plot. The starting point for investigations was a warehouse in the town of Beniparrel in Valencia owned by Marfishval, a fish and seafood wholesaler, as well as a clutch of other sister companies.

This company allegedly sourced illegally caught and smuggled tuna from three chief sources: Spanish fishing sources; a company called Red Fish SRL di Russo Francesco in Sicily; Malta Fish Farming Limited (MFF) or its owners in Malta. Marfishval and its sister companies then allegedly distributed the smuggled tuna to fishmongers and other sales points throughout Spain and beyond.

The Civil Guard wrote in their report that the tuna that came from MFF Ltd or its directors was transported from its place of capture to Valencia in trucks of a company called Express Trailers Malta.

Contacted for comment, MFF Ltd’s Giovanni Ellul replied via his lawyer, who wrote that the matter involved ongoing “court proceedings” and as such questions should be “submitted to the competent authorities.”

Franco Azzopardi, CEO of Express Trailers Malta, said in response to a request for comment that the company is “not aware of any ongoing investigation.” He also said that “no police or other investigatory authority ever visited the premises in relation to this claim.”

Asked to confirm or deny employing or engaging the driver named in the investigation (whose name is being withheld), Azzopardi wrote: “I confirm that in the period referred to we had no driver by the name of [name withheld] driving any of our trucks.”

After uncovering this Valencia racket, the Civil Guard started tapping the phones of those involved. This led them to the Murcia plot – the connection between the two plots, or rackets, was Red Fish, which, according to the Civil Guard, supplied both lines.

The investigative report said that the Murcia plot mostly involved companies of the Ricardo Fuentes e Hijos, and most of the allegedly illegally-caught tuna was sourced from Sicily’s Red Fish. The Civil Guard mention both Red Fish (as a legal entity) as well as Salvatore Russo (in his personal legal capacity or personality). Red Fish is owned by Salvatore Russo’s two sons.

Responding to questions, Salvatore Russo said he does “not play any role in Red Fish SRL.” He added that neither he nor any companies he is associated with have anything to do with “the operation conducted by the Spanish investigators and in general to fish smuggling, so much so that we have never received any charges in this regard.”

The 66-year-old native of Acireale, in the province of Catania, is longtime player in the fishing industry in Catania, particularly in the fishing and trading of swordfish and tuna. He is the sole owner of New International Fish, and he is currently undergoing proceedings in a Catania court as part of the carabinieri’s – this is the gendarmerie force in Italy – investigation called Oro Rosso (Red Gold). Russo was allegedly involved in the illegal tuna trade, something that also involved corrupt officials – Russo even allegedly managed to get back tuna that had been seized during port inspections on returning vessels.

The Civil Guard’s investigations of the Murcia plot are patchier because the racketeers had a mole in the Civil Guard who was allegedly leaking intelligence about the investigation. The Civil Guard wrote in their report that this even led to Jose Fuentes Garcia of the Fuentes group to change his telephone number and for the alleged racketeers to desist from talking openly on the phone. It also forced the Civil Guard to change some of the investigators whose identity was compromised and to change an incognito vehicle they were using to shadow the illicit activity.

The mole was eventually outed and he is currently being prosecuted.

The investigative report states that each of the companies investigated was involved in the tuna trade in a legal capacity, and separately in a parallel illegal operation.

All tuna caught, transported, and sold has to be registered on tuna catch document called eBCD. The eBCD documents the provenance of the tuna and every step of the way, from catch to fishmonger.

Those involved in the rackets uncovered in Tarantelo were using allegedly falsified eBCD to smuggle and trade in tuna. According to the Civil Guard, in some instances eBCD were merely falsified, and in others they were simply recycling eBCD. Sources said that in some instances eBCDs of, say, tuna dispatched to Japan were photocopied to move the same amount of illegally-caught tuna to Spain.

In yet other cases, the people moving the tuna would only show a delivery note, or transport documentation, and these would only bring out an eBCD – either falsified or recycled – if the cargo was subjected to inspection.

In response to Tarantelo, ICCAT last November expanded the rules on monitoring and control. There are now three layers of supervision – ICCAT-deployed regional observers as well as national observers who inspect, or observe, crucial stages during capture of the tuna, transfer, and slaughter of the tuna, and input the information in the eBCD. On top of that there is a National Authority that seals the farm cages as soon as the tuna is transferred into the cage, and then only opens the cages in case of emergencies or sickness, or prior to slaughter.

Yet talk of illegal fishing among sources remains widespread.

Additional reporting by Marcos Garcia Rey and Simone Olivelli.

This investigation is part of a collaboration with IRPImedia in Italy and Merca2 in Spain.

Donate to Investigative Journalism

Robustly researched, professionally delivered, and sustained journalistic investigations published on this website make a difference – and take much time, effort, and resources to produce. Victor Paul Borg relies on donations for income and to fund journalistic investigations. This website's donation setup itself is uniquely transparent, with targeted amounts that allow tracking of donations in real time on the page. Yet the modest donation amounts sought have not even been achieved. Contribute as little as €5 to sustain the only self-generated and active investigative journalism in Malta that makes an impact.