The Planning Commission sanctioned a building whose planning permit had been revoked by the court by latching onto a type of justification that the court itself had described as a "dangerous conclusion", this website can report after extensive research.

The Planning Commission is one of the planning boards of the Planning Authority that decide on applications for development.

Moreover, when it sanctioned the building 'as built' last June, the Planning Commission had imposed a fine. This has also now been cancelled by the same Planning Commission in a further decision last month.

The Court of Appeal – the final court in such instances – had revoked the permit in November of 2023 because it had more storeys than permitted in the Local Plan's policy map on height. The planning permit revoked by the court was initially granted to Francesco Grima, one of Gozo’s largest developers, although the latest application was put in by an applicant named James Zammit.

The block of flats sits amid a cluster of three other similar developments by different developers that are now transforming what was a quiet neighbourhood of Xewkija into a dense pocket of around a 100 flats along a new road.

The block of flats had been constructed by the time the court revoked the permit. Then, last June, the Development Planning Application Report (more commonly monikered as the Case Officer Report) recommended sanctioning by insisting that the height of the building was in line with policies – contradicting the court – and added that this had been clarified in a planning circular by the Planning Authority's Executive Council.

Newer buildings become 'commitment'

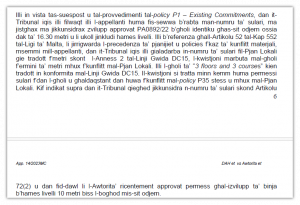

The Planning Commission which approved the sanctioning then went further than the report's assertions. The commission argued that three planning permits had been granted for five-storey blocks of flats in the same street, and that these were 'material consideration' (by way of commitment) that justified the sanctioning in terms of Article 72 (d) of the Development Planning Act. That article holds that planning boards have to take into account, among policies and other things, "any other material consideration, including surrounding legal commitments."

Below is an extract of the minutes.

All these three 'commitments' were planning permits granted after the appellants had appealed against the development in question. In other words, those permits to other developers were issued in the course of legal proceedings.

In fact, the building appealed against was the first multistorey block of flats to be granted permit in the new street where it is situated. The street had consisted, until then, of a few townhouses, most of them old, and a couple of open fields.

Yet the Planning Authority, instead of pausing decisions on new applications until the permit appealed against was decided, simply went on to grant three other permits for similar blocks of flats having same number of storeys as the approved building against which there was a legal challenge for revocation of planning permission.

The largest of these three other buildings – consisting of 44 flats and still under construction – belongs to the property magnate Joseph Portelli and two of his partners in Gozo.

Court criticizes justification by 'commitment'

When someone appeals against a planning permit, it is first heard by the Environment and Planning Review Tribunal. The tribunal enjoys little credibility in legal circles, and the Court of Appeal – which in turn hears appeals from the tribunal's decisions – regularly overturns the tribunal's decisions.

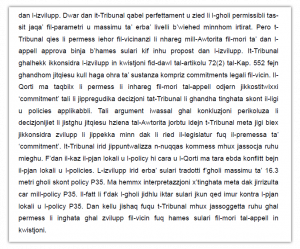

In this case, the planning tribunal had rejected the appellants' case at least partly for the same reason cited later by the Planning Commission. The tribunal had argued that a permit granted for a building across the street (the 44-flat block belonging to Portelli and partners already mentioned earlier) constituted 'commitment' under the same law, Article 72 (d) of the planning act.

It is an argument or reasoning that the Court of Appeal decried as a "dangerous conclusion". The Court of Appeal then overturned the tribunal's decision and revoked the permit. Here is an extract of the Court of Appeal's judgement.

The Court of Appeal in such cases is the highest and final court. Yet, as already pointed out, the Planning Commission then justified sanctioning the block of flats 'as built' by making the same argument that the tribunal had made, and this despite the fact that the Court of Appeal had characterized such argument as dangerous.

In so doing, the Planning Commission disregarded or paid no heed to the final court's decision. The Planning Commission is chaired by Elizabeth Ellul. Its two other members are Cornelia Tabone and Pierre Hili.

Jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights (the highest court in Council of Europe member states) suggests that such action – a public authority disregarding a court judgement – is a violation of appellants' fundamental right to a fair hearing.

Fine cancelled

When the commission had sanctioned the building 'as built' last June, a fine of €27,049 was imposed as part of the sanctioning. The applicant then asked for a reconsideration, this time to get the fine cancelled, arguing that the fine was excessive and unjustified because the developer had adhered to procedures and that construction was completed by the time the Court of Appeal delivered judgement.

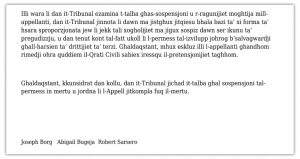

The fine was then rescinded last month by the Planning Commission. Here is an extract of the minutes below.

The reasoning hinges on the fact the planning tribunal did not suspend construction during the appeal and, furthermore, that the Court of Appeal then “did not suspend execution of works prior to the revocation of the permit.”

As already pointed out, construction was already complete, or virtually complete, by the time the appellants went to court.

As for the planning tribunal, it had rejected the appellants' request to suspend the works by arguing that the appellants would not suffer “disproportionate prejudice” if the works were not stopped, and this is because a planning permit is issued without prejudicing third party rights, and that moreover “it cannot be excluded that the appellants have other remedies in front of the civil court in order to put forth their pretentions.”

The Court of Appeal criticized the tribunal's line of reasoning, and held that it was faulty or wrong in law. Here is an extract of the court's judgement on the matter.

NGOs have for years been lobbying for a change in law so that construction works would automatically be suspended until appeals are decided.

In two bills presented in parliament last July, now subject to protests and debate and review, the government accepted the need for this change but then gave it a time-limit: suspension of works would expire if the Court of Appeal did not decide on a case within five months for whatever reason.

The court often takes more than five months to decide an appeal on a planning permit, and many times that is beyond the court's control – for example, if one of the parties is not found when court officials go to the given address to notify that party of the appeal filed, then the case would almost certainly take longer than 5 months in the Court of Appeal.

NGOs have decried other provisions in the bills. These include provisions that potentially give legal cover to decisions deviating from policies, and elevate (or give primacy) to circulars of the Executive Council. Other provisions in the bill on the planning tribunal hold that the Court of Appeal can no longer revoke a planning permit; that only the tribunal can establish facts of the case; and that the court, if it finds a tribunal decision wrong on a point of law, can only send the case back to the planning tribunal for fresh consideration.

This article is a follow-up of a journalistic investigation that was supported by S-Info and Repubblika, which forms part of S-Info, and co-funded by the European Union. It was carried out in collaboration with the environmental NGO Flimkien Ghal Ambjent Ahjar.

This article is a follow-up of a journalistic investigation that was supported by S-Info and Repubblika, which forms part of S-Info, and co-funded by the European Union. It was carried out in collaboration with the environmental NGO Flimkien Ghal Ambjent Ahjar.