This website and its partners have received multiple reports of illegal fishing for tuna near Libya in this year’s fishing season. In recent days one of the sources said that a group of 12 Libyan purse seiners – this refers to vessels that catch tuna live in purse seine nets, which is then towed to tuna fattening farms – have now been served with what is known as PNCs, which stands for potential non-compliance notifications. He alleged that illegally caught tuna went to different farms around the Mediterranean, particularly Malta.

Malta has the highest tuna farming capacity in the world. Its farms were this year allocated a capacity of 15,703 tons by the EU, almost a third of the EU total of 49,405 tons.

Malta was also mentioned at the beginning of this year on Croatian media. A fisheries inspector told a Croatian newspaper that an unspecified amount of tuna without eBCD (catch document) was initially procured by an unnamed Maltese tuna farm from Libyan boats, and then transported to a farm in Croatia, where the fisheries minister allegedly held meetings intended to regularize the tuna. The Croatian ministry for fisheries has denied the allegations, which have led, or contributed, to ongoing legal proceedings by the EU Commission against Croatia.

In this summer’s tuna fishing season, which ran from the end of May to the beginning of July, the multiple, unconnected sources talked to this website and its partners – IRPImedia in Italy and Merca2 in Spain – in the course of investigations into impunity caused by stalled court proceedings in Spain, and Malta, that stemmed from the Tarantelo investigation. In Operation Tarantelo, Spain’s Civil Guard described a multimillion racket in illegal fishing, smuggling and trading racket spanning Malta, Italy, and Spain.

The website last week published an investigation into the protagonists that featured in Tarantelo, and the impunity caused by the stalled proceedings.

Fifteen Libyan purse seiners were authorized to catch tuna this season, and twelve of them took part in a Joint Fishing Operation. In the Joint Fishing Operation, these 12 were authorized to supply the catch to the fattening farms of Malta Fish Farming Limited (MFF Ltd) and Ta Mattew Fisheries Limited, which belong to the same owners. The 12 vessels had a combined catch quota of 1.8 tons of tuna, while the farms of MFF Ltd and Ta Mattew had a quota around double that figure.

Yet the sources alleged that on some occasions some of the Libyan purse seiners had no regional observers on board. And on other occasions, the observer simply put down whatever figures the boat’s captain or farm operators told him without independent verification.

One of the sources provided specific information on a particular fishing and caging event. The source alleged that tuna caught illegally by three Libyan purse seiners (which he named) was delivered by a towing vessel named Sea Bull to the tuna fattening farm belonging to Ta Mattew Fisheries on 19 June 2022.

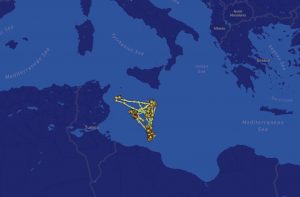

Given this highly specific information, this website attempted to corroborate the source’s allegations, starting from vessel tracking on Marine Traffic website.

Of the three Libyan purse seiners mentioned by the source, which are listed among those 12 boats in the Joint Fishing Operation document, no data could be found on one of them on Marine Traffic. As for the other two, the limited movement on Marine Traffic was inconsistent with fishing. There was also a third Libyan purse seiner that showed similar patterns of movements as the other two.

All of these three appeared on Marine Traffic tracking system at Malta’s Grand Harbour on 14 June, and then on another two or three occasions the following week, without any movements in-between. There was only one sailing event on Marine Traffic throughout the tuna fishing season: on the early evening of 28 June, a few days before the end of the fishing season, all of them left the Grand Harbour within the same hour and made a direct trip south to their home ports in Tripoli and Al Khoms in Libya. (These vessels are not being named here because attempts to contact their owners for comment were unsuccessful.)

This pattern of movement recorded on Marine Traffic lends itself to various possible analytical scenarios, but it does not prove or disprove anything.

The Automated Identification System (AIS) could have been switched off, or malfunctioning. Or the boats could have installed an AIS transponder prior to the first event, on 14 June at the Grand Harbour.

Moreover, Marine Traffic only tracks vessels via AIS. There is a second tracking system, the Vessel Monitoring System (VMS). Both systems use satellite tracking – AIS has been designed as a collision avoidance tool, allowing vessels to see each other; VMS is employed by national government to monitor fishing activity. More accurate data on boat movements can only be had by superimposing and cross-referencing the data from both systems, yet this website had no access to VMS data.

As for Sea Bull, which is a towing vessel, its data was more consistent throughout the fishing season. Marine Traffic showed that on the morning of 19 June it spent a few hours at the tuna farms around 6km offshore from Marsascala, where fattening cages of Ta Mattew Fisheries and another three farms are situated. This was the date of the alleged caging given by the source.

This website then tracked Sea Bull back in time and found that, a day earlier, it picked a carrier cage from another towing vessel. Going further back still, patterns of movement suggest that this second towing vessel itself got the carrier cage from yet another towing vessel eleven days earlier. (These two vessels are not being named because attempts contact their owners and request comment were unsuccessful.)

According to EU regulations, transfer of carrier cages from one towing boat to another has to have prior authorization from State authorities. Questions were sent to Malta’s Department of Fisheries to ask if any such authorisations were granted to those boats, but the department did not answer.

The same question was sent to Giovanni Ellul, director of MFF Ltd and Ta Mattew Fisheries. He was also asked to confirm or deny whether the tuna caged on 19 June 2022 was illegally caught by a group of Libyan purse seiners. Other questions pertained to his and MMF Ltd's alleged role in Operation Tarantelo.

A reply was sent by his lawyer, who wrote that “your queries relate to allegations of recent illegalities and court proceedings” and, “in this regard, we are of the view that any questions on the matter should be submitted to the competent authorities, to whom my clients will be forwarding your request.”

Similar questions were sent to ICCAT, which was also asked why ownership data for the Sea Bull had been removed from ICCAT’s website – on 23 June, ownership of the Sea Bull pertained to MFF Ltd, but at some point later, the ownership details no longer appeared.

ICCAT responded that as an “intergovernmental organization” it only “corresponds with the governmental authorities of its Contracting Parties” and that “all publicly available information can be found on our website.”

Questions were also sent to an official within the ministry for fisheries in Libya.

“All catches [of tuna],” he wrote, “were observed by ROP (ICCAT regional observers) which they had been embarked on board of all the targeted fishing vessels.” He added that “Libya didn't receive any notification from ICCAT” that the VMS of any of the boats was switched off.

By this point, this website and its partners had exhausted all possible avenues of corroboration. And given the lack of answers and the lack of access to additional data – reports of observers, VMS tracking data, and additional data held by Maltese authorities (for example, any authorisations issued for transfer of carrier cage from vessel to vessel) – at this stage the attempt to corroborate sources’ specific information or allegations has remained inconclusive.

All of this also draws attention to the lack of transparency by ICCAT and – more importantly – the Maltese department of fisheries, which failed to answer to repeated questions.

The department is under parliamentary secretary Alicia Bugeja Said, who was appointed last April. Questions were sent to the parliamentary secretary’s spokesperson as well as Bugeja Said directly. Neither responded.

Bugeja Said, who studied conservation and anthropology, used to be extremely critical of the tuna fattening industry.

Earlier this year she received a pre-election donation of €2,500 from MFF Ltd, and another €1,500 from Azzopardi Fisheries, which is owned by the same owners of another company that has tuna fattening farms in the north coast of Malta.

This website also spoke to Alessandro Buzzi, the WWF’s expert on bluefin tuna, who highlighted, among other things, “issues with regional observers, especially in the quality of their reports.”

A source close to ICCAT separately alleged that observers’ video footage is not being properly scrutinized within ICCAT.

Yet for Alessandro Buzzi, the prevalence of illegally-caught tuna in fattening farms is evident in growth rates of tuna that some fattening farms claim.

“The growth rates are crazy,” Buzzi told this website. “You put 10 fish in a cage and you state that they increased their weight by 200 percent. In reality the farm would have actually put in 20 fish in the first place.”

The tuna caught in the wild and put in the fattening cages – where they are fed to increase their fat to meat ratio that is favoured in the sushi and sashimi market – weigh on average over a 100kg each. The price of wholesale tuna meat in Japan is more than €35 per kilo, and that means that a single tuna is worth thousands of euros.

ICCAT is currently reviewing the growth rate with a view to imposing limits on growth rates that fattening farms can claim.

“Activity surrounding the tuna farming industry is complex and hard to monitor,” Buzzi said. “We keep adding regulations, but illegalities keep happening, so it’s really hard to keep pace.”

Article by Victor Paul Borg. Additional research by Marcos Garcia Rey.

Donate to Investigative Journalism

Robustly researched, professionally delivered, and sustained journalistic investigations published on this website make a difference – and take much time, effort, and resources to produce. Victor Paul Borg relies on donations for income and to fund journalistic investigations. This website's donation setup itself is uniquely transparent, with targeted amounts that allow tracking of donations in real time on the page. Contribute as little as €5 to sustain active, investigative journalism that makes an impact.